A few weeks ago, I began reading On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good. And then, as embarrassing as it feels to admit, I gave up reading it. The prose is excellent, the topic timely, and yet it felt like another task on my burgeoning to-do list. The very nature of reading a book promising clarity on women’s desire to be good enough felt like a step on that very journey.

I didn’t want to be good. I just wanted a break.

A male co-worker–whom I platonically adore–commented on how hard juggling work and family can be and asked, “What did we do before we were able to work remotely?”

To which I replied, “We had women.” Women who escorted themselves politely out of the workforce to juggle the running and mending and cooking and scheduling and emotional checking in with their families and neighbors and the masses.

“I’d like to be known as a household manager,” said one friend, checking all of those boxes in her mind.

My own reality skews sharply towards social progress. My husband is the primary household manager. He makes doctor’s appointments, stays home with feverish children, cooks dinner, and in general keeps the household running far smoother than I might be able to accomplish (without giving up my job).

“I wish I had a husband who did all of that,” a coworker exclaimed.

“It’s nice,” I say somewhat wistfully.

So why does it still feel so hard to be well? Why is it still seemingly impossible to give up the pursuit of perfection? Why has work become just another frontier for proving ourselves?

Husbands pick up slack at home so wives can lean in, running ragged to rise in the ranks. Amazon moms play second fiddle to Pinterest moms, though we’d never openly convict each other of doing something wrong. And I’ve been known to tell my children’s teachers, “I don’t have time to volunteer, but I do have money to buy extra school supplies.”

We’ve traded in homefront aspirations for boardroom goals, giving up the morality of a perfect residence, clean and clothed children, and organic dinners for success at work.

“My work is made possible by my husband’s ability to take care of everything at home,” I admit, knowing that without that ace in my pocket my professional status might falter. Knowing that if I had to ensure the kids got to all of their activities in time, I would need to turn down meetings and projects, my visibility shrinking.

“You can’t have it all. Not even close. You can have some of it, but not all at once,” one seasoned therapist told me, much to my Enneagram Type 3’s chagrin.

“Why are you getting your MBA again?” asked my mother after one particularly fraught day of studying was done and gone.

“So I can do and be more,” I replied tersely in my mind. But more of what?

“So my daughter can see that women can do anything,” I counter inwardly. But if anything is possible, why doesn’t art count? Why doesn’t keeping a home–setting the table for our daily bread, decorating for Halloween with the now ragged garland of bats–feel as impressive as earning six figures?

My own mother sewed our Halloween costumes and sacrificed her career to stay home with us for years, the price of daycare having pushed her out of the market. She taught me to turn garage sale finds and thrifted gems into the holiest of homes, to sing and laugh in equal measure.

What will my daughter see in me, I wonder? Will it be different when she’s grown? Will women have turned away from the pursuit of goodness, the drive for perfection?

For now I keep on waking and working out and getting kids off to school and staying late to send one more email and logging on after the kids go to bed.

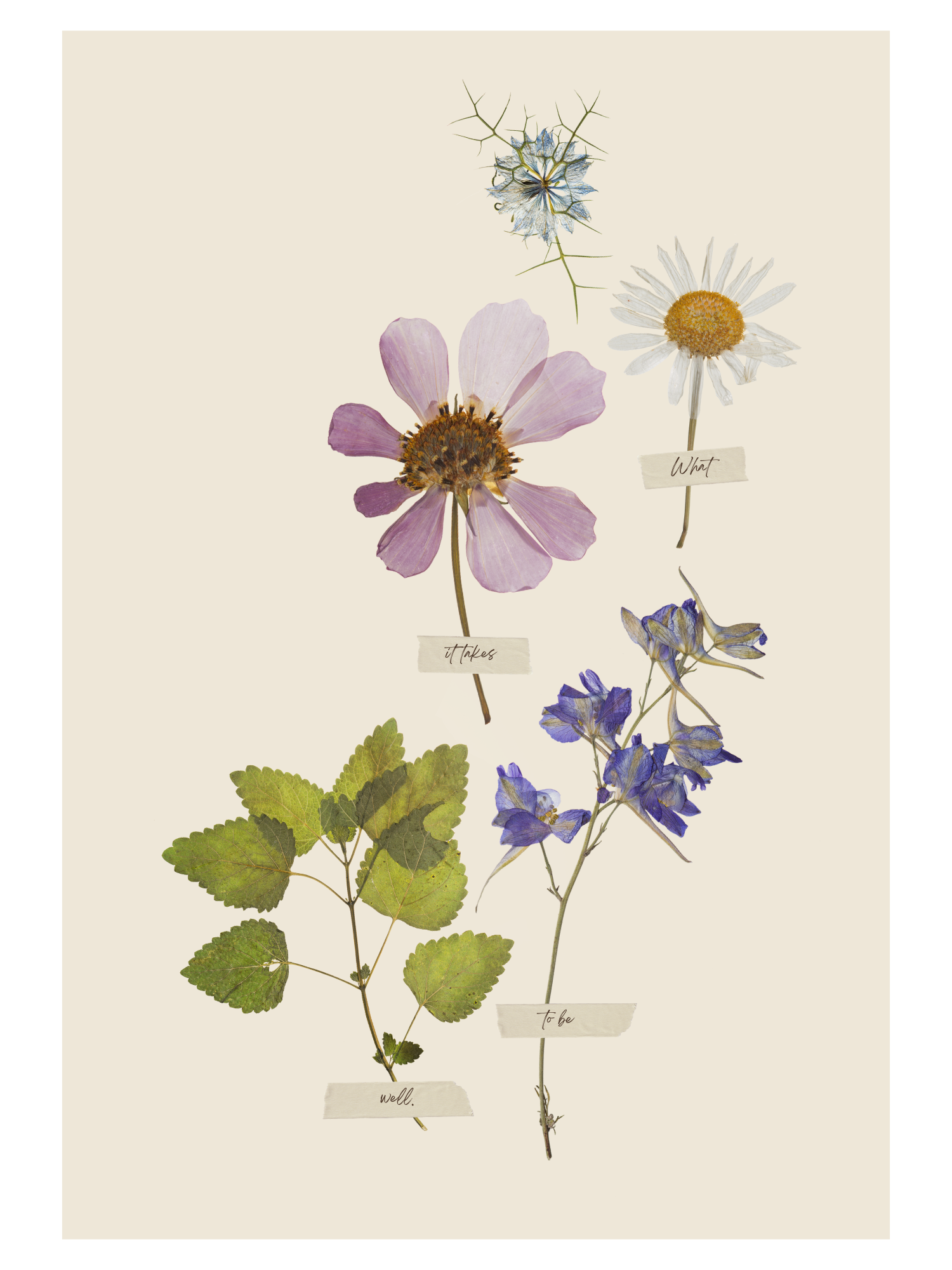

One day, things will be different. One day, I’ll fully grasp what it takes to be well.